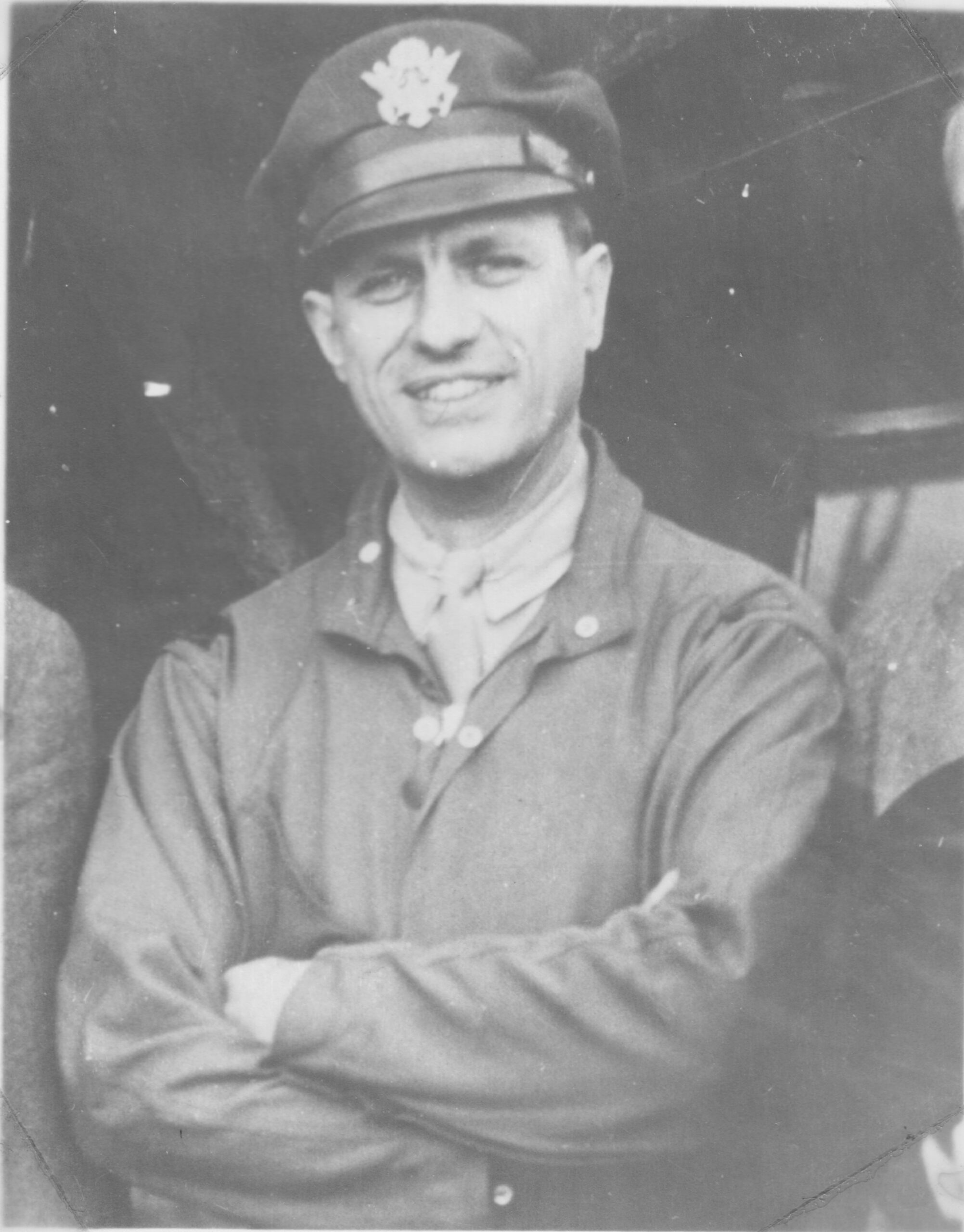

Brig. General Frederick W. Castle

Medal of Honor

Medal of Honor Citation

He was air commander and leader of more than 2,000 heavy bombers in a strike against German airfields on 24 December 1944. En route to the target, the failure of 1 engine forced him to relinquish his place at the head of the formation. In order not to endanger friendly troops on the ground below, he refused to jettison his bombs to gain speed maneuverability. His lagging, unescorted aircraft became the target of numerous enemy fighters which ripped the left wing with cannon shells. set the oxygen system afire, and wounded 2 members of the crew. Repeated attacks started fires in 2 engines, leaving the Flying Fortress in imminent danger of exploding. Realizing the hopelessness of the situation, the bail-out order was given. Without regard for his personal safety he gallantly remained alone at the controls to afford all other crewmembers an opportunity to escape. Still another attack exploded gasoline tanks in the right wing, and the bomber plunged earthward, carrying Gen. Castle to his death. His intrepidity and willing sacrifice of his life to save members of the crew were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service.

4th CBW “The loss of General Castle”.

It was with great sorrow that all units of the 4th Bombardment Wing received the news that our Wing Commander, General Castle, was definitely lost on the raid to Babenhausen on December 24th, 1944.

General Castle had taken permanent command of the Wing in the middle of April 1944. Prior to that time, he had served as acting Commander for several months.The loss of General Castle was a grievous one not only for our wing, but for the entire Eighth Air Force. He came to England originally as A-4 of the 8th Bomber Command under Lt. General Eaker. He served with great distinction in that position until June 1943. He was then transferred to the 94th Bombardment Group at his own request. Under General Castle’s command, the 94th Bombardment Group made an enviable record, receiving a presidential citation for a bombing raid on Brunswick, Germany in January, 1944. The imagination and energy displayed by General Castle resulted in many innovations which improved the effectiveness of our bombing operations.

During his service in ETO, General Castle had risen from the grade of Captain to that of Brigadier General. His decoration included the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters, Distinguished Flying Cross with two oakleaf clusters, Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Croix de Guerre and the order of Kutuzov- second degree.

Source: REEL B0896 AFHRA Maxwell AFB.

Brigadier-General Frederick W. Castle.

Our stalwart leader has paid the supreme sacrifice. Though of average physical stature, he was head and shoulders above us in leadership and in his ability to get results. He led us by sharing all he experiences of war with us.

We shall continue to be led by his example though he is gone. His spirit affirms “Keep ‘em flying” until there is peace, and tyranny is defeated. He often challenged us in this vein: “The only excuse for a Bomb Group is to get bombs on the target - - - results count.” This can be applied to all of life for all of us.

Chaplain William M. Miller.

Source: REEL B0166 AFHRA Maxwell AFB.

General Castle.

Brigadier-General Frederick W. Castle was killed when the flying Fortress in which he was flying was shot down in flames by seven Nazi fighters near Liège. He was leading the Third Air Division on Christmas Eve against Germany when, in an attack by Me 109’s, two of the Fortresses engines burst into flames and oxygen tanks ignited. Though the heavy bomb load was threatened, Brigadier-General Castle would not order the release of the bombs because allied soldiers and civilians were below. Apparently determined to be the last man to leave the airplane, he ordered the Pilot to bail out, sending him forward for his parachute. The Fortress then spun down to 12,000 feet, where a wing fuel tank exploded, sending the bomber to destruction. The bodies of Brigadier-General Castle and the Pilot were found in the wreckage. General Castle, who was on his 30th combat mission, held the Silver Star, the Croix de Guerre (for helping the French Maquis with supplies from the air), the Soviet order of Kutuzov for leading a flight of shuttle bombers from England, and the Legion of Merit. Formerly he was chief of supply for the 8th Bomber Command, but was at his own request transferred to a combat assignment as a Flying Fortress Group commander.

Brigadier-General castle joined the 94th Bombardment Group 22 June 1943. General Castle, then Colonel Castle, commanded the Group until 14 April 1944 at which time the Colonel became commander 4th Combat Bombardment Wing (Prov).

General Castle was one of the Pioneers of the Eighth Air Force. He came to the E.T.O. 4 February 1942. The General was assigned to duty as A-4 Officer Eighth Air Force and performed the duty until this assignment to the 94th Group.

Through the Generals superior organizational ability and his outstanding leadership and example his Group and station made a record that was enviable among the heavy Bombardment Groups of the Eighth Air Force. The General's leadership and his Group contributed immeasurably to the success of the Regensburg mission 17 August 1943 which resulted in a Presidential Citation for the 3rd Air Division.

Again on 11 January 1944, the results of General’s untiring efforts to beat the Hun were realized. For this mission to Brunswick the Group received the Presidential Citation. The General flew fifteen missions while he was with the 94th Bomb Group, among those who flew with him, a common remark was “This must be a tough one today, the Colonel is flying”.The General was and still is genuinely respected, affectionately admired, and loved by the officers and men of this Group. There is not any doubt in the minds of the men of this Station but that his motto was: “Results count”. He preached it and - more important he practiced it.

Herschel D. West

Major, Air Corps,

Adjutant.Source: REEL B0166 AFHRA Maxwell AFB

Public Relations Office.

Brigadier-General Frederick W. Castle, one of the US Eighth Air Force pioneers, died heroically December 24, when a B17 Flying Fortress in which he was flying was shot down in flames by seven German Messerschmitt fighters near Liège, Belgium.

Commander of a Bomb Wing of the Eighth Air Force, General Castle was leading the Third Air Division in an attack on Germany when a single Nazi fighter attacked from head on, shattering the plexiglass nose and wounding the lead navigator. Spitting gunfire, six more Me 109’s came in for the kill. Two of the Fort’s engines burst into flames. In the waist, oxygen tanks were ignited threatening explosion of the aircrafts heavy bomb load. The General would not order the bombs salvoed because allied soldiers and civilians were in the area below.Lowering the wheels to cut flying speed, the Pilot ordered his crew to bail out, saying over the intercom, “This is it”. General Castle, trying to hold the lurching, burning bomber in control on two engines, was fighting to keep the aircraft level enough for the men to bail out. Apparently determined to be the last man from the plane, the General told the Pilot “Get Out”, sending him forward for his parachute.

The doomed Fortress spun down to 12,000 feet, where a wing tank exploded, sending the bomber on its final tight spiral to destruction.

Of the ill-fated crew, four who parachuted have returned safely to England, two are still hospitalized and two apparently blown from the plane, were killed. General Castle's body and the Pilots were found in the scattered wreckage southwest of Liège.

The mission was General Castle’s 30th combat operational flight. At no time had the General been ordered to fly combat missions, yet as often as possible when a difficult operation had to be flown he managed to appear in the plane. Enlisted airmen recalled how, after rough missions, the General always ate with them at their mess, still in flying gear.As commanding officer of a Fortress Group, General Castle received the Silver Star for gallantry while leading a Combat Wing attacking an aircraft plant at Oschersleben, Germany, in September 1943. The plant was among the most vital assembly units in Germany, and the flight was the deepest daylight penetration of the Rheich up to that time by the Eighth’s heavies. The attack was successful despite vicious enemy interception and poor visibility.

The French Maquis were supplied from the air under General Castle’s direction. For his efforts in their behalf, The General received the Croix de Guerre. (Units other than General Castle’s also dropped supplies to the Maquis.)

In the Soviet Union, General Castle received the order of Kutuzov, second degree, for leading a flight of shuttle bomber from England, attacking war factories the Germans had moved east, and landing in Russia.He also held the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters and the Air Medal with three clusters.

Arriving in England in February, 1942, with general Ira C. Eaker and three other officers, General Castle helped lay the ground work for the Eighth Air Force. Starting with practically nothing but determination, these men created what was to become America's greatest aerial striking force.As chief of supply for the Eight Bomber Command, General Castle was cited by General Eaker, at that time Commanding General. The official commendation read: “I have never seen the A-4 (supply) function better performed then in the organization you created.”

Upon his own request, General Castle, Then a Colonel, was transferred from his own relatively safe assignment as a staff officer to a combat assignment as a Flying Fortress Group Commander.

A West Point graduate, class of ’30, General Castle received his flight training at Kelly Field, Texas. In 1934 he resigned from the Air Forces to work with the Allied Chemical and Dye Company. Later, until recalled to active duty in January 1942, he was assistant to the president of the Sperry Gyroscope Company.

Source: REEL B0166 AFHRA Maxwell AFB

Air Power in this war and the following peace.

The record in this war.

Under the awful compulsion of war, the basic lessons of air power have been learned quickly and well by the American people. The lessons had to be learned quickly , for we were still arguing the theory of air power when Pearl Harbor and Singapore suddenly taught us the facts of it – almost too late. Luckily for our national existence, Russia and Great Britain stoutly held their lines around the Black Sea, and in Egypt, and on the English Channel, while we frantically improvised in the Pacific and built the great machine of war which has turned the tide for the United Nations.

Even after many of the lessons of military air power had been demonstrated to us by our enemies in their first treacherous onslaught, we still had basic questions to settle for ourselves. The most difficult of these questions was what proportion of our economic and military effort to put into tactical air power and what proportion to put into strategic air power. Since in any case a very high percentage of our national war effort was to be concentrated in the building of airplanes and the training of air crews, this was an important question indeed.

Air power had not yet been used strategically in any great force, and there were few lessons of experience on which to base our decision. Germany had smashed Poland and France with a tactical air force, used mainly in close support of ground troops. This force had then turned against England, with the strategic objective of destroying England’s air force at its bases and in its factories. The failure of the effort was resounding, because Goering used for the purpose aircraft designed only for tactical employment. The lessons learned from this were purely negative; it taught us how not to use a tactical air force.

In the Pacific, too, the only important lessons that had been learned had to do with tactical or strategic-military employment of air forces. The battle line were so far from both Japan and the United States that with the bombers then available no strategic-economic bombing was possible by either side. Pearl Harbor was a brilliantly executed strategic blow, but had its effect only on the immediate military situation, and taught us nothing of economic air war.

However, our Air Staff knew that Great Britain had already decided to build many heavy bombers fore strategic-economic air war aimed at the heart of Germany. This was a natural decision for Great Britain to make, for the use of strategic-economic warfare has played a big part in all of the important wars fought by that maritime nation. Although an American naval officer, Captain Nahan, had expressed most lucidly the grand principles of strategic war during the greatest age of naval power, it was the British who applied these principles most effectively in war and in peace. As Great Britain and her potential enemies became more industrialized, the importance of the strategic-economic side of war became more obvious to her; thus naval power’s most importance use in World War I was the blockade of the Central Powers, denying them access to many of the most needed materials of war.

It was natural then that as air power came of age, Britain’s War Cabinet studied the possibilities of strategic air war. When World War II burst upon the world, Great Britain prepared behind the barricade of the Channel to inflict on Germany the kind of air blockade which would be one of her greatest contributions to the cause of the Allies. There was no argument in the Air Ministry when night bombing was selected instead of day bombing. England had no choice but to start bombing at night in view of initial advantages Germany had obtained with the defeat of France. Lacking sufficient numbers and time, England could not attempt to break through that bulwark in daytime until America was fully ranged on her side.

But heavy decisions had still to be made in the United States. The need for a large number of defensive fighters was obvious. Also obvious was the need for a certain proportion of light, medium and heavy bombers to hold our enemies at a safe distance from Hawaii and from Australia. Further, there was no question as to the need of long cruising aircraft to assist in the defeat of the U-Boat. But these measures of defence were not enough. There was still the great question of what kind of air power should be used carrying the war offensively to our enemies.

These were the momentous questions to be decided:

- Should we build a great fleet of war planes, British or American type, to fly and fight at night with the British air fleet?

- Should we discount the value of strategic bombing and concentrate on building enormous quantities of tactical bombers and fighters, leaving to the British whatever strategic bombing was to be done?

- Should we agree that America’s great industrial and military might should be turned to the problem of successfully attacking the heart of Germany in daylight?

The decision was made – a major proportion of America’s air power would be devoted to battling it out with the Nazis in the daytime over the enemy’s own country. A whole book could be written on the reasons and the significance behind this one decision. It was one of the most serious ever to be made in the history of war. The lives of millions of Americans and of Englishmen and of Russians and their Allies depended on its rightness. If the decision were wrong, a tremendous proportion of the economic power of America had been directed into the wrong channels, and would have to be redirected at a waste of manpower and materials into other channels, while men died lacking the proper air power and the materials of war they needed. As it was, the doubters still doubted, and the advocates of strategic bombing of Nazi Germany were frequently called to justify their position and were frequently faced with diversions from the original plans.

But in the meantime the U.S. Air Force and the aircraft industry went ahead with the job. Huge new aircraft plants were designed and built, and hundreds of thousands of works trained to man them. Scores of bomber training bases were constructed and organized, when our eager young airman learned the complicated technique of flying and fighting their four-motored craft. Staff officers arranged with British Staff officers and our own Engineers Corps the construction of the aerodromes and supply bases in England.

Extraordinary progress was made, a good deal of it due to the help and cooperation of the RAF Bomber Command and the Air Ministry. Because RAF airdromes already operational were transferred for use of the American bombers, a small token force of B-17’s was able to make its first preliminary jab against the GAF on August 17, 1942.

But the battle went hard. Losses and replacement difficulties kept our force low, and in October the largest force we were yet able to put in the sky amounted only 107, and by December this had not increased.

One of the major reasons for the slowness of our start was the decision to make a major Anglo-American effort to open the Mediterranean and invade Italy. This decision was undoubtedly necessary. Shortage of shipping made highly important the shortening of our routes to Russia and the Far East. And in addition, a large scale battle rehearsal was needed to prepare a great Anglo-American army and its leaders for the final supreme effort against the Atlantic Wall. But this decision to strike in the Mediterranean did entail diversion of a high proportion of America’s trained heavy bomber units to bases in Africa, where they could be used on the main only for tactical or strategic-military bombing. Those left in England to strike against the core of German air power were faced with odds they had not counted on.

The air offensive against Germany, therefore started slowly but start it did, and no one can now question the great results obtained. In some ways they are even greater than the most optimistic and far-seeing students of air power could have hoped. In April, 1943, only some 400 heavy bomber sorties were flown over Nazi occupied territory, the largest force on any one mission amounting to 123 B-17’s and B-24’s. The force was so small that no attempt could be made to break into Germany itself, although effective work was done against U-Boat bases in the occupied countries. But by June the force had grown and the great attempt was made. In that month, on June 22nd, some 250 bombers battled their way through the German fighter opposition to bomb a synthetic rubber plant at Huls near the Ruhr. Other attacks had already been made on the coastal cities of Bremen and Kiel, but Huls was the first attempt to break through the outer screen into the industrial heart of Germany.

The attempt was costly, but not so costly as to disprove the theory nor to make impractical further attempts. After a breathing space and a regrouping of forces, another attack was launched on July 28th and this time a force reached all the way to the aircraft plant at Oschersleben near Brunswick, in the heart of Germany. By that time the Eighth Air Force was still growing slowly but had managed to dispatch in one month nearly three thousand sorties. The Germans were thoroughly frightened by this apparition of air power threatening the war manufacturing industry of the fatherland. Our air reconnaissance photographs showed the feverish attempts being made to build up their fighter production facilities. In the meantime, Britain’s night bomber strength had also increased and the RAF was dropping thousands of tons of bombs on Hamburg, Bremen, Cologne, the Ruhr, and other industrial centers. The fight of strategic bombing against the German air defences and the German industrial system was growing to a climax.

It became obvious that the first great task of the air forces was to defeat the Luftwaffe by shooting it out of the air and by destroying its breeding places on the ground – its aircraft plants and its airdromes. This task was not only necessary to enable strategic bombers to continue their mission of destruction of the German war industry, but also top prevent the defensive air forces of Germany from becoming so large as to successfully oppose an attempt by our ground armies to land on the western shores of Europe. It had already become too apparent that no landing could ever be made on a heavily defended shore if the air above those shores was not controlled by the invading power.

So the battle went on. Our forces were skilfully used in jabbing attacks from all directions. Tactical lessons were learned in the skies over Helgoland, over Bremen, over the Low countries, over France. These lessons were learned fast, and the rate of learning them was such as to keep the enemy from developing sufficient counter measures to defeat us. As in all wars, time was of the essence. It was the rate with which we could bring our units to England, equip them and train them for combat which was the decisive factor. Additional forward guns had to be placed in the bombers to ward off new types of attacks developed by Goering’s Squadrons. Crews had to be trained in new tactics. Feverish efforts had to be made in the US to supply the necessary replacements of aircraft and crews and to organize the new units required. Long range gasoline tanks had to be developed and fitted to the supporting fighter aircraft whose gallant pilots were flying deeper and deeper in support of the bombers – deep enough to go to any aircraft factory in Germany. All this tremendous effort had to be done at a speed sufficient to win success before Goering had organized enough new fighter Squadrons to beat down our efforts and to set up an impenetrable barrier.

The great campaign grew in tempo. On July 29 the Focke-Wulf aircraft plant at Warnemunde on the Baltic was destroyed. On August 17 the large Messerschmidt factory at Regensburg was knocked out on the first shuttle raid to Africa. On October 9th Focke-Wulf plants at Anklam and at Marienburg (in East Prussia) were devastated. On other days, several aircraft supply and repair bases were hit. In October, November, and December the weather worsened, restricting to some extent the number and type of missions, but in January 1944, the offensive got fully under way again, and soon the Luftwaffe’s ability to operate effectively by day was practically neutralized.

Off course, a price had to be paid. But the losses suffered by the Eighth Air Force in the attacks on Bremen, Regensburg, Marienburg, Anklam, Tutow, Brunswick, Leipzig, Stuttgart, Magdeburg, Warnemunde, Friedrichshafen, Posen, and the other centers of German aircraft production, repair, and supply were light compared with the ultimate overwhelming saving in time and life to the Allies.

The desired first objective can be said to have been attained in March of 1944. In that month some 12,000 airplanes loads of bombs were dropped by our -17’s and B-24’s, an increase of 5,000 over January. The GAF had reached a low ebb, and was declining further rapidly, so that attention could now more and more be paid to the vital oil production centers, the ball bearing industry, and the tank and vehicle factories, on which the life of the Wehrmacht depended. Side lines could also be taken on, such as attacks against robot bomb launching sites. And while the GAF declined, our forces grew lustier. In the historic month of June, 1944, 28,000 heavy bomber sorties were flown, not only continuing the air offensive against the war industry of Germany, but at the same time, with the RAF, more directly supporting the ground troops and the tactical air forces in hundreds of tactical and strategic-military missions against airdromes, hun batteries, bridges and railroad marshalling yards in the invasion area. The German communication system broke down completely in the face of the air onslaught. Our ground forces, heavy though the fight was on the beaches, were able to establish their unloading and supply bases with practically no danger from the skies and no rapidly concentrated opposition from enemy panzer divisions. Once having consolidated their beachhead, the Allies were soon able to break through with the decisive results we now see.

The lessons from the air campaign of Europe will require many years and much gathering of facts to be fully learned. At this moment scores of scientists are preparing to analyse the effect of the air invasion of Germany. Many detailed questions must be answered as to the effectiveness of the various types of bombing efforts against German industry. These are typical:

- Which oof the various “bombing through the overcast” techniques, used during bad weather, were the most effective in their result?

- Was the bombing of German aircraft assembly plants more effective than the bombing of the German aircraft engine plants in affecting aircraft production?

- When did the attacks on the oil industry begin to seriously affect the enemy defence system and strategic plans?

- What was the effect on German aircraft, motor vehicle and tank production of the bombing of the ball bearing industry?

- How effective was the timing of our attacks against various segments of German industry? Should we, for instance, have shifted sooner or later from emphasis on aircraft plants to emphasis on the oil industry?

These and hundreds of other questions must be answered before we will know in detail how air power should be again employed if it ever has to be in another war in our generation. But in any case the main lesson has already been learned. This lesson is that air power is no longer the “over-assertive and brawling adolescent” it may have been when it was fighting for recognition in a sceptical pre-war world. Air power carried out the mission given it better than was promised.

Now a great new air offensive is being mounted against our enemy in the Pacific; this time with several new types of aircraft and new tactics, based on the lessons of the European war. There is no question that Japanese resistance will collapse under the overwhelming power soon to be brought against her. The end is, in fact, so obviously near that the United Nations are now engaged in the task of discussing how a just and progressive peace may be established in the world – a peace which will last long enough to enable mankind to go up a few rungs higher in the never ending evolutionary climb.

In these discussions a crucial question is how air power will be used in the organization for peace.

Air power in peace.

In my first article a summary was given of the results so far achieved by air power in this war, especially that air power used in a strategic-economic warfare against the heart of the Nazi military system. The immediate military lessons learnt where sketched only briefly for it is obvious that it is too early to draw any exhaustive conclusions from what was has so recently been accomplished. Furthermore, the art of air warfare is still rapidly changing, so that the lessons of the immediate past can only be used as a rather general indication of future developments.

But we cannot wait too long to draw our broad conclusions as to the use of air power in peace. Air power is now of such consequence that it may well be the most important implement of national policy of the future. Certainly military men cannot have much to say as to the national diplomatic objectives for which that implement is used. But advice can well be received from the airmen who built the implement as to the techniques of its employment, as to its limitations and as to its future trends of development. This article will outline some of the lessons the war has taught us on these subjects and some of the considerations which should be the basis for future studies.

Certain assumptions must be made, for it is impossible to discuss air power on the technical side without assuming some of the conditions of its employment. First we must assume a national policy which will recognise the necessity for an Air Force in being, just as was recognised during the past 100 years the necessity for a Navy in being. This is a logical assumption, even though the necessity for an Air Force in being was not recognised before World War II began. It is logical because if any lesson on air power has been learned in this war, it is that this country can never again be without an air fleet, any more than it can be without a sea fleet.

Another assumption is that the nation will be will make provisions to keep that standing air fleet relatively up-to-date technically. The word “relatively” is used advisedly, since a military force can only be judged on its technical efficiency in comparing it with forces available to its possible opponents In peacetime, no more money is usually spent on research and development than that necessary to keep the instruments of war as sharp as those of any of our potential enemies. Judgement, of course enters a great deal into the decision as to how far to go is this respect, since a small force, highly efficient, may well be equally in effectiveness to a much larger force which is not technically up-to-date. In general, however, we can assume that the United states will keep well up in the van all technical developments in aviation because of our leadership so far in that field.

A third assumption is that the United states as a national policy will recognise the necessity for enough power. Before World War II it was fashionable to consider “power” an all its synonyms as ugly words. We were ashamed that in South America our nation was known as the “colossus of the north”. It was considered obnoxious that many other nations of the world were using what we called “power politics”. Our ambition was to set such an example for the world that power would no longer be a factor in international relations, although we compromised with this ideal in adopting agreements with England and Japan and the other maritime nations which still gave us a naval fleet equal in size to the only other great naval power in the world, Great Britain.

We must assume, however, that despite this recent history in which we have tried to remove power as an instrument of national policy, our lesson has been learned well and we will never again wittingly allow ourselves to be put into a position that forces us to accede to the wrong ambitions of some other nation, or combination of nations, because we have denuded ourselves of all power or the ability to use our power. No good American, of course, would wish that power for its own sake will ever become an objective of our national policy, or that our people of or our government will ever become so forgetful of our national heritage of ideals of freedom and tolerance that our power would be used to impose any arbitrary will on weaker neighbours.

But quoting Mahan, the American naval captain who so lucidly explained the function of sea power in the last century: “if time be, as is everywhere admitted, a supreme factor in war, it behoves countries whose genius is essentially not military, whose people, like all free people, object to pay for large military establishments, to see to it that they are at least strong enough to gain the time necessary to turn the spirit and capacity of their subjects into the new activities which war calls for”.

If this were true in Mahan’s time, how much more through is it now, when the factor of air power makes initial surprise so much more possible and the speed of war so much greater. Fortuitous situations have given us the time we needed in all our past wars - in the future we cannot expect luck always to be on our side, especially with the potentialities of air power still not completely developed. Let us not forget Pearl harbour.

One basic fact which must stand out in any discussion of what we are learning in World War II is that a method of war has been discovered which no longer depends mainly on attrition for the final decisive results. True that attrition is still a large factor in the results that are ultimately being attained, for it was the tremendous ability of Russia to stand great attrition, and still to inflict attrition on our enemy, which saved her during the critical months of 1942 when Germany was grinding through her inner defences. But if attrition alone had been dependent on for final victory, millions more would have died and the war would have been prolonged many months if not years. Russia depended on attrition only because she had to. With a good part of her economic system overrun by her enemy, her aircraft industry could concentrate only on fighters and short range bombers, and even many of these weapons had to be obtained from our Allies. Time and geography being on America's side, we could use a bomber force built even after we had entered the war to strike at the heart of German power and to put attrition in second place in our strategic plans.

What of the future? No nation that is seeking her ends with war-like means will ever again rely on attrition as the means of defeating her enemies, it having been demonstrated so conclusively that air power no longer makes this necessary. The whole object of the grand strategy of the future will be to break through the enemy's air defences to strike at the very source of the military power - the aircraft factories, the oil plants, the vehicle factories, the steel mills and the communication centres.

The outlines of the world security organisation to protect us against such aggression are now being drawn. No plans have yet been published except brief summaries. It is plain, however, that whatever the plan adopted, it will involve the allocation of an international police force to the decisions of an international executive body, which will order its employment more or less rapidly, depending on the degree of delegation of power which the participating nations are willing to give the executed body. Where will these international forces be located and of what will they be composed in the way of aircraft, naval vessels and ground troops? No attempt will be made to answer these questions, since they lie in the province of foreign policy, but certain characteristics of air forces will be pointed out which must be borne in mind when our representatives, and representatives of our Allies, make decisions on these questions.

First, it must be pointed out there is no such thing as a purely defensive Air Force, as contrasted with a purely offensive Air Force. It is true that England, to a large extent, broke the German blitz in 1941 with the defence fighter force. However RAF Fighter Command would be the first to admit that the subsequent protection of England against not only bombers, but also flying bombs, could not have been undertaken effectively only with fighters. Modern bombers (and flying bombs) have enormous tactical and strategic mobility. Defensive measures against them or have increased also in their efficiency, but the trend of development indicates that we can never be confident that the fighter and the anti-aircraft can be depended on for more than one part of the job. If the factories producing the German bombers and flying bombs, if the aerodromes and launching sites from which they flew, and if the supply depots which kept them going where all left un-attacked during 1943 and 1944, the defensive forces in England could never have coped with the problem of protecting her own military establishments and production centres.

This is a very important point, and one which cannot be stressed too strongly in any discussions of the part air power will take in a national defence system of the United states in the future. Even past history, when air power was not a real factor to be considered, should teach us the lesson that peace loving nations can easily fall into the error of believing that there is such a thing as a purely defensive military establishment. This type of thinking has come to be called “Maginot Line mentality”. This mentality, not wanting to offend neighbouring nations with any show of force which might be used offensively, hopes to retire behind the static defences or fixed fortifications, manned by a “defensive” ground force made-up largely of infantry, and supported by “defensive” Air Force made up largely of short range fighters, and a “defensive” Navy made up of a few battleships, cruisers, and submarines. It has become a cliche to say that the best defence is an offence, but a lesson has to be learned over and over again. The reason why this lessons must be learned at period intervals is that sometimes the philosophy is discredited by an improper use of offensive tactics due to the changing weapons.

A tragic example of this is the failure of the French offensive-defensive tactics of 1914 and 1915. The French staff college, studying the lessons of 1870, had imbued the army with the idea that in another invasion the invader could only be repelled by men psychologically prepared to attack at every opportunity. The spirit was there, but the weapons were lacking. The result was a tremendous slaughter of French manhood, as Frenchman desperately counter-attacked with their bayonets, small arms, and small cannon against the heavy armament with which Bismarck and Von Bulow had equipped the German army.

When these strategies and tactics became too great a drain on French (and British) manpower, World War I settled into a long period of attrition from which it only emerged when the German army broke down under the weight of the new hordes brought from America and under the hunger wrought by the British blockade. French military minds thought they had learned new lessons of war from this sad experience, and under the leadership of Gamelin, the French army was reorganised in the philosophy that the best defence is a defence. Under this philosophy France fell under the attack of 1940 more quickly than any great nation has ever fallen.

America's ideals are peaceful, and we hope to cooperate in the world whose pattern instead of peaceful development and progress, not only for our own nation, but for all others, towards true political and economic freedom. But while seeking our ideals, let us not unrealistically leave ourselves open to the same tragedies other less fortunate nations have recently suffered. It is more important now than ever that we achieved a proper philosophy of national defence for no longer does geography give us the great attention is it did in the past.

Insofar as air power is concerned, this means that we must recognise the ability of a potential future enemy to strike suddenly and surely at the very heart of our defensive power and to repeat these strikes with great rapidity, unless we ourselves have the means to strike back in the same manner. It has become fashionable to say that Douhet was wrong in his concept of a sudden mass aerial war, where great air armies clash and within a space of a few days decide the issues between the contestants. As a matter of fact, Douhet was proved absolutely right by the events in Europe. Germany's neighbours were conquered in the space of only a few weeks by the employment of the short range aerial weapons available then. England across the channel missed the same fate largely through the over-eagerness and mistakes of Hitler and Goering, and the unshakeable courage of the British people and their leaders. The fact that the war did not end abruptly in that tragic summer of 1940, nor later when the Russians were so hard pressed, was that air power was still only in its very beginnings with war on a global scale, geography was still much on the side of the defenders.

During this one war the effective striking distance of air forces has grown from less than 500 miles to more than 1,500 miles, and without the theory of diminishing returns raising its ugly head. Increased range gives several advantages, some obvious and others not so obvious to the layman. The most obvious advantage is that from a particular based along arrange bombers can reach more of the important military and economic establishment of the enemy.

In addition, the longer range bomber has more choice of routes in penetrating to its target, and in withdrawing to its base, thus increasing the problem of the defence. Thus a bomber of 1,500 miles striking radius, based near London, can approach Berlin from many more different directions, using a choice of many land and sea routes, compared with a bomber of only 500 mile radius.

Furthermore, the several air bases is necessary for the attack of a particular region can be separated more, thus reducing the chance that weather conditions will keep the entire force immobile on any particular day, and also again causing greater dispersion of the enemies defensive measures. The basis for the Eighth Air Force are concentrated in a relatively small part of England. If the newer type of bombers, with their 1,000 mile greater striking radius, had been available two years ago, those bases could have been spread from the northern tip of Scotland to Southampton, with great advantages to us and proportionate disadvantages to the defences of the Reich.

In the future, our potential enemies will know these modern air power facts had may some-day be able to build a long range bomber striking force. This being true, let us guard carefully against any appearance of “Maginot mindedness” in our thoughts for our future defence. Whether we depend only on our own strength or defence, or whether we combine with other great allies to developing combined defensive system, let us be sure that the air power which we allocate for the purpose is composed of all the elements necessary to attain and genuine defence against aggression. Let us be sure that any potential enemy will see us bristling not only with the anti-aircraft guns and fighters necessary to stand up against an initial assault, but also fleets of bombers to strike back and reduce subsequent assaults to the minimum.

The next great question which must be equal share in discussing the disposition of air forces in the security plans for the future is that of the logistics of present and future air forces. Here it is too easy to forget the trends of the immediate past, and use as our lessons only isolated examples, from this arguing to false conclusions as to the future.

It is of course, true that in area warfare, as in all other warfare, logistics (“that branch of the military art dealing with the transport quartering and supply of troops”) is one of the greatest controlling factors in strategic planning. The principles of logistics are, in fact, so simple at any given time that we forget sometimes the enormous differences in logistics some slight change in technique or invention may make, changing the equations by which we make our logistical calculations. Thus, in 1942 bomber forces could only bomb effectively some 500 miles from the basis available to them. From this it was simple to establish where those faces must be if we were to attack the targets we wish to attack. From this again it was simple to calculate the total expenditure of men hours an materials necessary to prepare those bases and get the supplies to them.

But suppose we add 1,000 miles, or 200%, to the range of the bombers, as has been done recently, and put this new factor in our equations. The enormous difference this factor makes in our logistical planning is astounding. It not only shortens greatly the routes over which our supplies must go to the basis to be established, but it also opens up great new possibilities from the ground forces strategic standpoint, since it may eliminate the necessity for expanding efforts on capturing many air bases is still in enemy hands.

To sum up, the logistical trend is on the side of bomber forces. Everything that is now happening in the development of long range aircraft is in a direction of reducing the logistical problem, and of making more sudden and effective the results to be obtained from the appointment of air forces to strike against the heart of the enemies military and economic power.

In converting to plans for peace, we find this means that the great air bases set up under the plans for national or international security will change their relative importance as the technique technical possibilities of aviation are further explored. Thus, one airbase which today may be strategically valuable and also have saved supply routes, may tomorrow come under possible attack from several new sources and have vulnerable supply routes. Another base, farther back, hitherto only valuable as a way station or repair base, may take on new importance as a defence centre, as the bombers and fighters increase their ranges. Therefore, present and future security arrangements must be dynamic rather than static, with necessary changes in a disposition of air bases and the forces to garrison those bases, as new technical developments change the aspect of air power. Our Singapore’s corridors, and Pearl Harbours of the future must be properly armed, and properly located.

The author believes that the factors discussed above, the offensive-defensive characteristics of air forces and the changing trend of the strategy and logistics, based on increasing range of bombers, are the most important facts of air power which the American people must have in mind in making plans for future security. However, there is another factor to some extent outside the province of a discussion of the technique of employment of air forces, which bears emphasis: air intelligence.

In peace time, America has been loath to give any important place to economic or military intelligence. This was due to our sense of relative security, protected as we were for so many years but oceans on the east and West and the possession of great natural resources. We were satisfied to obtain information about the military establishments and plans of other nations largely through voluntary submission or fax at international conference tables. It is true that we were not entirely unaware of the dangers which faced us before 1939, but we were still unwilling to take measures which would give us the real facts as to the preparations for war of nations which we instinctively felt were our enemies. The American people were satisfied, and therefore our general staff had to be satisfied, in obtaining their facts only from what was willingly given by our potential enemies, or allies, to our diplomatic and military representatives, and also from a few business men and journalists who were able to deduce some of the plans which later resulted in war.

Can we rely on such measures in the future? It is true that preparations for war cannot possibly be hidden under modern conditions. If the peace loving nations of the future maintain any kind of an organisation for security, potential aggressors must makes such preparations for attack that they cannot be misunderstood by the well informed. But, on the other hand, propaganda and the other shuttle means of lulling into false security could again be used in the future as in the past. It seems, therefore, that a well thought out mission machinery for ensuring complete knowledge to all nations of the types and quantities of weapons manufactured by each would be one of the best assurances of the proper development through the years of all necessary security measures on the part of the united peace loving nations. In this respect, air intelligence would be the most important, for the first great attack by any aggressor nation would be by air. By knowing of the preparations for any such attack thoroughly and well in advance, the threatened nation could be make the necessary provisions against it or bring aggressor to account in accordance with any machinery set up for that purpose.

The thoughts expressed above cover an extremely wide scope and are only suggestive of much which should be studied as soon as both the European and Pacific wars have been concluded. In any case, these broad considerations should be taken into account even now, as a statesman of the United nations draw the outlines of the future organisation for peace.

Source: REEL B0896, AFHRA Maxwell AFB